BCLS: Adam Koppel

“The last 20 years has been one of the best times for basic science discovery.”

Healthcare investing is a three-body problem. No simple or closed form solution exists to predict how science, medicine and capital markets will move. Finding the intersection of these independent variables is technically difficult: “I knew the business, biotech, medical and scientific languages…I was well positioned [as an investor] to find the intersection of healthcare and business.” reflects Adam Koppel, Partner at Bain Capital Life Sciences (BCLS).

Yet Koppel’s path to learning these “languages,” and becoming a leading investor was, in his own words, “circuitous.” He entered college as a physics major, but soon changed tack: “At various parts of your career you think you're smart…but often you can identify people that are at a different level. Math and physics people are thinking at a different level. .” Koppel continued studying physics but earned a degree in the history of science—learning philosophy, history and how to write and communicate effectively.

His decision to start an MD-PhD at UPenn was driven by a passion for science, rather than a desire to hang up a shingle as a practicing doc: “I loved studying medicine and understanding the human body. I was drawn to the brain: how does such a complex system develop so reproducibly?” A desire to answer this question launched Koppel into highly productive graduate study. Working in Jonathan Raper’s lab, he was part of the team that cloned and characterized the initial members of the semaphorin family and the associated receptors—molecular “stop signs” that guide axons during brain development. The work made Koppel, and the rest of the Raper lab, recognized within the neuroscience community; he envisioned becoming a neurosurgeon-scientist and opening his own lab to study neurodevelopment.

Yet before committing to the physician-scientist path, Koppel hit the pause button: “The PhD work went well, and I finished several months early…I had some time before starting residency.” On a whim, he enrolled in the Wharton School of Business: “I found it interesting to learn about balance sheets and business strategy but had no intentions of ‘taking it anywhere.’ It was simply a way to spend time.”

Balance sheets aside, what he learned in business school caught him by surprise: “I loved my time at Wharton. I really connected socially and enjoyed the business environment even more than I did in medical school or the lab.” He also started to question the reach he could have as an individual physician-scientist: “I saw that healthcare businesses can have a broad impact on patient care. If you develop a drug or device that helps millions of people in need, you can affect an order of magnitude more people.”

The allure of having broader impact led Koppel to a role as a healthcare consultant at McKinsey, and then as a public equity investor at Bain Capital: “I didn’t know anything about investing, but they agreed to teach me from scratch.”

As an MD PhD MBA, Koppel was now “fluent” in the languages of science, medicine and business. He thrived as a public investor: “If you know enough, you can identify a mistake in the market—an overreaction that blows up a company's market cap unfairly. We call these companies ‘fallen angels.’ When I was a public investor, I made a lot of my outsized alpha through this approach.” He cites BCLS’ investment in Dicerna as an example of how the firm recently leveraged this strategy.

Since 2016, Koppel has been a Partner at BCLS. He sits on the board of directors of Cerevel, Solid Biosciences, Foghorn Therapeutics, Areteia and Cardurion. He previously served on the board of directors of Dicerna, Aptinyx, Trevena and PTC Therapeutics.

In our interview he reflects on the challenges of MD-PhD training and steps through the BCLS approach to biotech investing. He shares advice for new investors and mistakes that companies should avoid heading into 2024.

Above all else, he stresses that learning to be an effective investor or operator takes time. Like learning a new language, trial and error are requisite. Yet there is another essential ingredient—one not easily quantifiable: “You need to be a good listener—this means being physically and mentally present. Part of that involves keeping an open mind. If you can suspend your own biases, you are more likely to think outside of the box.”

Below is an interview with Adam Koppel, MD PhD MBA, Partner at BCLS from December 2023:

1. What was your first taste of science and medicine? Briefly, what about this initial experience drew you in?

My story is a bit circuitous. I was an undergrad physics and math concentrator at Harvard College. I came back to school sophomore year and my advisor—who was a pretty famous theoretical physicist—said: “Adam, you're a nice guy. You're a smart guy…but you're not physics smart.” He encouraged me to find another field within science. This was in 1988, and he [advisor] suggested molecular biology. I didn't really know what molecular biology was at the time. My advisor also gave me a second piece of advice, which was to learn how to write and communicate while in school, because in the real world most people don't know how to write well. I continued taking physics courses, but I did a major at Harvard called History and Science. In addition to learning about physics, I studied the philosophy and history of physics throughout the enlightenment and scientific revolution.

At various parts of your career, you think you're smart…but often you can identify people that are smarter at a much different level. This was my experience in college—people in physics and math were just a different order of magnitude in terms of intelligence. The rather blunt but well-meaning advice from my advisor enabled me to also learn history and philosophy while still doing some physics. The experience gave me a broader perspective. I was able to explore, especially in my senior year, and that was great. After college, I went directly to do the MD-PhD at UPenn, with a focus in molecular biology.

I did not start college considering medicine; but my father and grandfather were physicians. I was always interested in the human body and the complexity of physiology. However, as an undergraduate I did not truly understand what it meant to “be a doctor” or to “practice medicine.” I did however really like the concept that you could get a dual training…as an MD-PhD you can uniquely practice a profession or trade [medicine] while also doing science.

2. What was your MD-PhD training like?

I met a lot of people that I liked and appreciated during my MD-PhD. I learned how to interact with different types of individuals. A key piece of advice I received was that one shouldn't overly focus on any one particular mentor, you should have many mentors if you meet a lot of people, you can triangulate what you learn from different skill sets. I took this to heart during the MD-PhD; a path where you meet and learn lots of different things.

On the MD side [of training] I really liked studying medicine and understanding the human body. I was drawn to the brain, and the question of how such a complex system develops so reproducibly.

There are trillions of neurons and quadrillions of connections, and yet the vast majority of us have “normal” brains. How does that happen? I got really fascinated by the complexity of the human body, including other systems--cardiovascular, renal, hepatic, respiratory. At the time, immunology was in its infancy but even then, you could see how natural selection shaped the development of the immune system.

I loved the concept of learning basic science and medicine in parallel. I also enjoyed the interaction with patients, physicians, house staff and nurses. As a medical student it was a real exercise in “psychology”—how do you get stuff done when you are not in a strong position to influence [patient care]. I enjoyed both the academic and social aspects of medicine. However, I found that I didn't love spending hours upon hours in the hospital. For me, it was a very draining atmosphere. I also found patient care to be a bit repetitive—with many hours focused on the logistical rather than the academic. On the science side, I loved thinking about the next experiment: planning how to efficiently generate data. I also liked writing the papers, which came naturally to me.

What I didn't love about the PhD was doing experiments [manually]. I was good at thinking through what the experiment needed to be, and at interpreting data. But that process of coming in every day and [physically] doing all the molecular biology, microscopy and sequencing was very repetitive. Today, a lot of things [like sequencing] are fully automated.

[on some high points from PhD training]

[Experiments] were so monotonous that I would often play golf with my lab mate while running gels on low voltage. We would then come back to lab in the afternoon and finish the experiments. I actually got a whole paper out of this [way of working]. Once, I ran a gel at such a low voltage and for so long [while playing golf] that I separated two protein segments that had dimerized . This dimer had not previously been appreciated. We later found it had biological relevance. [collapsin-1].

During my PhD I was very focused on science—a hardcore grad student. I joined Jon Raper’s lab—who was actually Corey Goodman’s first post-doc. Jon was early in his tenure at UPenn at the time, but the lab was well established with some high profile papers on neurodevelopment.

I was fortunate to come into a lab that was in the process of creating its strong reputation, but had its lineages traced to some important work in brain development. We cloned some of the signaling molecules and the associated receptors that control how the brain is patterned: how neurons know where to make connections or synapses. The field, at that time, was focused on the attractant molecules; our lab believed that there must be molecular repellents as well. We identified the first of these molecules—cloning collapsin-1, which was the first in a family of guidance molecules known as the semaphorins . It was such an exciting time.

3. How did you end up earning an MBA from Wharton?

The PhD work went well, and I finished a several months ahead of schedule. I ended up having some extra time before starting my planned residency in neurosurgery.

I was thinking of going back to work in lab and beginning my post-doctoral research. However, I found that Penn had a loophole [at the time] where for every semester you were enrolled as a student, you could take an additional “free” course at any school. At that point, I had been at Penn for 6 years and thus had 12 credits. Mainly due to its reputation, I decided to take courses at Wharton School of Business. I found it interesting to learn about balance sheets and business strategy but had no intentions of “taking it anywhere”, it was simply a way to spend the year before I started residency. I had no plan.

At Wharton, I had a great finance professor named Franklin Allen, who suggested that I explore business more thoroughly. He suggested I go work in healthcare at McKinsey and see what the business of healthcare was really like. I started in January of 2000.

4. Differences between academia and business/consulting world?

Part of the reason I decided to go to McKinsey was because I loved my time at Wharton. I really connected socially and had a lot of fun. I enjoyed the environment even more than I did when I was in medical school. In fact, I am still quite close with my business school friends to this day

When a young person is going through career decision, they often want to be where they feel like they belong. I found these same types of people at McKinsey and felt comfortable there as a result. Being in the hospital all the time did not appeal to me; and in science often you are working alone. I found “business” to be much more team oriented—often you are working towards a large goal in a given timeframe. I really enjoyed this team-driven aspect.

I ended up staying for almost four years at McKinsey—I enjoyed this time a lot and saw that healthcare businesses can have a broad impact on patient care. If you develop a drug or device that helps millions of people in need, you can have an order of magnitude more impact than by being an individual clinician. I also had encouragement from my wife, who is an oncologist, to stay in the business world and to not go back to residency.

5. What brought you to Bain Capital, and what early allowed you to succeed there as an investor?

After over three years at McKinsey, I got called to interview for a venture capital firm, which was really my first exposure to investing. Long story short, I ended up not getting the VC job. However, during the interview process I really felt like I had the skillset to become a good investor. Four or five months later, I got a call from Bain Capital Public Equity. They proposed applying the private equity methodology (of doing diligence and evaluating companies) to the public markets. I didn’t know anything about investing—even the difference between credit or equity—but they said: “perfect.” They really just wanted my expertise in healthcare, and agreed to teach me the investing component from scratch.

I decided to join Bain Capital on somewhat of a whim—but I have been fortunate to learn a lot and succeed here. This story brings up a piece of career advice that I always give. There are two ways to succeed in one’s career. One path is to be laser focused on exactly what you want to do and have it all planned out—like being a great physicist or surgeon. In this case, you have to really excel and love that one specific thing. There's another approach, which is to be good in a couple different areas and find the intersection of these strengths. In other words, be one of only a few people that knows how several variables are moving and uniquely position yourself to find the “intersection.”

At Bain Capital, I found myself in this position. I was not the best scientist, McKinsey consultant or even medical student—though I was very good at each. But I knew the business, biotech, medical and scientific languages. I was well positioned at the intersection of healthcare innovation and business. I could communicate with parties on all sides and bring them together—at the time this was very unique.

6. What were some of the early investing principles you learned at Bain Capital?

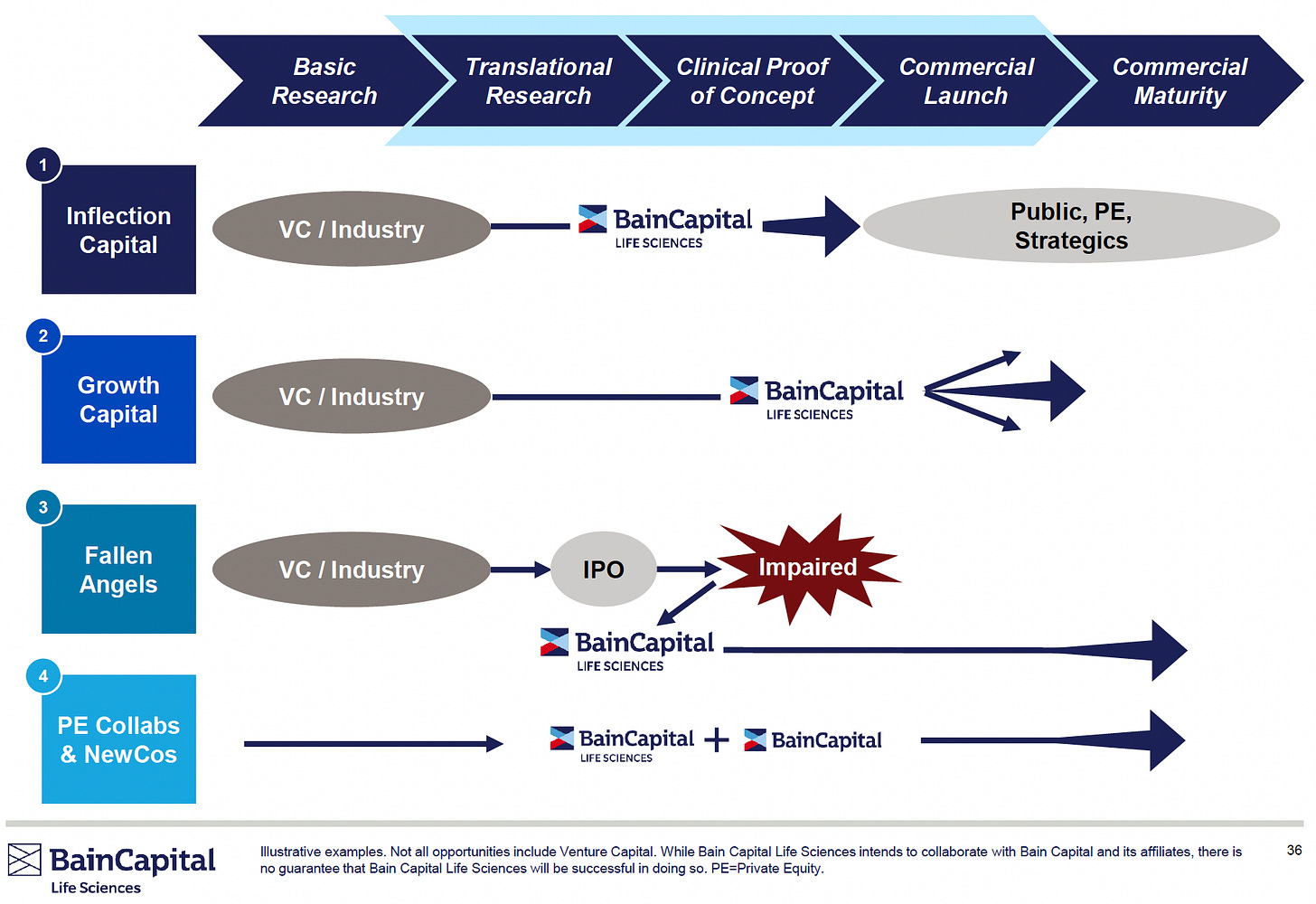

You don’t want to be in the business of predicting if Pfizer will beat or miss by a penny next quarter. We really want to consistently find alpha in the market. We have four archetypes of investing.

The first is to supply inflection capital—the so-called “crossover investment” that gives funding to companies prior to them going public. These companies will then hopefully go on to produce important clinical data. We were one of the first handful of funds to make this strategy work back in 2005-2008. Others include Baker Brothers, Deerfield, RA Capital, Westfield.

A second mechanism is to supply growth capital to companies with clear visibility to revenue—in biotech this means that they've already de-risked the clinical data and are ready for commercialization. Our capital would go towards expanding their business: geographic expansion, label or indication expansion, furthering developing their pipeline or platform.

We have been very successful with the third strategy – Fallen Angels. A great investor told me back in 2005 that the best way to be a public investor is to know 60 or 70 names well in your sector. Inevitably 20% of them are going to blow up every year. Often, these companies blow up for a good reason and you don't want to invest in them. If you know enough, you can identify a mistake in the market—an overreaction that blew up a company's market cap unfairly. In these scenarios, one can identify a new path forward to help them reset and regain value. Importantly the risk-reward is more favorable since these stocks are down 70 to 90%, but there is often enough clinical information to understand what went wrong. We call these companies “fallen angels.” When I was a public investor about 15 years ago, I made a lot of my outsized alpha through this third approach. An example here is an investment we made in 2017 called Dicerna, which was pursuing siRNA therapeutics in rare disease. Harvard Business School wrote up a case on this company and our investment.

Finally, there are private equity collaborations: an example here is Cerevel. Biotech is hard because it is a different type of investing. It's not widgets, it's not financials, it's not industrials…you can't rely on basic business instincts to make investment decisions. Our goal in this last bucket was to combine a team that all with years of experience in the life sciences market with a team that is expert in scaling global private equity. A subset of this strategy is called a “spin-co NewCo.” In this scenario, we take assets from a larger company that are not being developed but have positive clinical data. We then “spin out” a set of assets and create a NewCo centered on these drugs, capitalize and help run it. We’ve done this now several times with companies like Springworks, Cerevel, Cardurion, Aiolos and Areteia.

These are the four areas that I think are most conducive to reproducible alpha creation.

7. What are some encouraging trends that you are seeing in biotech today on the science side? What about the macroenvironment?

The last 20 years has been one of the best times for basic science discovery. Tens of billions of dollars from NIH or capital markets has supported great science achievement. An example would be how pandemic funding supported development of mRNA vaccines…this led to a Nobel Prize in 2022 for work that was done in 2000 or 2001. There are lots of examples of how discoveries or technologies from the 90s or early 2000s are now becoming great medicines: ADCs, GLP-1s, siRNA are some other examples.

[on macro trends in biotech and healthcare]

What does the ecosystem look like? Major secular trends like a growing middle class and global demand for better healthcare have been consistent and robust. People want to live healthier, more fulfilling lives. It’s our belief that the most effective way to deliver better health care is through innovative products: drugs, medical devices, diagnostics.

Global improvement in health will not be through having bigger hospital systems, or more surgeries. These are inefficient, expensive, and low-margin ways to distribute healthcare. Comparatively novel therapeutics or diagnostics can have 30 to 50% EBITA margins.

There exist 20 to 25 large global drug companies that have already spent billions of dollars building out commercial infrastructure—sales, marketing, distribution, payer relationships. What these companies are missing is a continuous supply of innovation. Scaling up internal R&D at these companies is not enough, nor is it efficient for their businesses. Once these large companies lose intellectual property protection, they have a great need to replenish their pipelines to maintain market and pricing power. This dynamic is made more acute by the Inflation Reduction Act (Please use another example) This dynamic makes the type of investing we do—innovative small to midsize clinical-stage companies—very fulfilling. There is a demand both at the level of the consumer [patients] and at the level of the big companies that may acquire and eventually commercialize these new products.

These are the positives. But the problem is that we are now in a real cycle change—save for the last three weeks between Thanksgiving and the end of 2023) where our market has done well. A week before Thanksgiving 2023, you had a 70% derating of the XBI. It peaked at $174 back in 2021, was at $65 around Thanksgiving, but is now around $80. As a result of this cycle change, a lot of “tourist” investors have run away from the sector. However, in the preceding years this influx of capital was creating too many companies—around 100 new biotechs per year for 5 years. There are now 850 public market biotech companies, many of which started with over capitalized and overvalued balance sheets and whose investors have now “run away.”

In 2023 there are fewer investors chasing after more ideas. This could be construed as a negative, but if you are an investor you can do well by capitalizing on strong secular trends and a weak moment in the cycle. This is actually the ideal time to be an alpha investor in our space.

8. The recent acquisitions of Cerevel and Karuna are exciting for the neuropsych space. How did you approach this space, which has seen so much failure in the past?

We look for investments with real markets and unmet medical needs. Number one: you need a market—is it an indication or disease that you can create a market around? A negative example here is the ultra-orphan rare diseases. Over the past 5 to 10 years, I think the market overplayed these a bit—because they thought it was easier to get FDA approval. We [Bain Capital Life Sciences] always had the approach of identifying diseases that have decent sized markets. It’s great that there are all these potential solutions for ultra orphan diseases and rare cancers, but prior to the pandemic there was relative underinvestment in common diseases that affect millions.

Point two is that you need to have an effect that is differentiated from the existing standard of care. Often there are cheap alternative standard of care treatments, so it is crucial to prove superiority. We have looked hard to identify assets that treat disease in a way that existing standard of care does not.

With respect to neuropsych—these are disease that affect an extraordinary number of individuals. We are now seeing clinical evidence [from Cerevel/Karuna] that muscarinic subtype drugs are working better than other atypical antipsychotics in treating diseases like schizophrenia [SCZ], agitation and psychosis. This is a new target [M4] with a therapeutic profile better than anything that's out there now. In neuropsych, or any space, we ask—will it work, will it sell and what’s it worth? All of these are informed by market size and efficacy over the standard of care. Answering these questions, is how you ultimately get consistent returns as an investor.

Another very competitive area is I&I and we have invested in companies like Nimbus, Upstream, Aiolos. With respect to TSLP and Aiolos, which we created with Atlas, we felt that the management team was very strong. The asset itself is differentiated—with q6 months administration for asthma—and that really separates it from other products on the market.

9. Briefly, what is a biotech (public or private) that you think serves as a paragon of an impactful company?

Vertex and Regeneron are two of the best examples of pure biotech that have just crushed it. Gilead and Celgene have also done great things, a generation earlier. I’m biased of course [as an investor] but I also love Nimbus and Cerevel.

The public markets have been somewhat discouraging, what is one short piece of advice you would give to clinical stage private biotechs/operators in this environment?

I have five learnings that I share with my LPs about the mistakes I've made throughout my career, which are also common mistakes that biotech companies also make:

· First is balance sheet strength. Do not leave yourself exposed to balance sheet risk, and do not leave yourself exposed to capital market uncertainty. You have got to have the balance sheet to get you through major value creating events.

· Number two: it's all about management and board. If a company has a bad management or toxic board culture, it will destroy potentially good assets.

· Number three is to always have clear value creating events. We are in a space that is often pre-revenue…companies need to have a great understanding of which catalysts build value. These are not minor ones like “finishing enrollment,” or having “10 patients of phase 1b data.”

· Number four is to respect the complexity of human biology. Physiology is complicated and as smart as you think you are, Mother Nature will always get you in the end—unless you're really careful. Biotech leaders, and investors, must accept that every time you test a drug or medical device the exact answer may be a surprise.

· Lastly, respect “competitive intensity” in the market. As soon as anyone sees a good clinical result for a particular asset, tons of other companies are going to come out of the woodwork trying to replicate that data and bypass intellectual property. To succeed in 2024, one must have strong clinical data differentiating factors that drive market adoption.

What advice would you give younger members of your team about good investor? Are there certain practices one should adopt when approaching each investment opportunity?

There are a few basic checklist items that I always run through. This includes deprioritizing companies where you can’t understand the time or capital it takes to get to an inflection point—a value creating event. You also need to structure the investment to maximize upside and truncate downside. Other points include ensuring a good management team. These points are all negatives—meaning that if a company doesn’t hit these checklist items you should de-prioritize.

But on the positive side you need an investment thesis to prioritize companies. With my team, I emphasize differential insight or unique perspective. This insight could be with respect to a pipeline, future free cash flows, multiple indication expansion or platform value. One could also have insight on a whole indication or disease—for example that the obesity space will explode. Another point of differential advantage on the private side could be around deal access or structure.

[How do you develop differential insight or deal access?]

Part of differential access is due to the individual investor or firm reputations. I think younger investors coming through are often rushing; and that they can come up with this ultimate deal. But often it takes time, experience and luck to come up with that great investment. It often cannot be rushed. I would say [to new investors] that it takes time to build a reputation.

Differential insight is based on reading the literature, going to scientific meetings, thinking creatively and rigorously. But you also need to be a really good listener—it’s not just about sitting in front of a Bloomberg screen or the NEJM. I also remind my team members to be present—physically and mentally. Part of that involves keeping an open mind and being receptive to new things. You have to be able to change your mind—this was the case with Cerevel’s M4 agonist in SCZ or GLP-1s in obesity. If you have an open mind and can suspend your own biases, you are more likely to think outside of the box and learn novel ideas.

12. Anything you are reading in your free time?

Empire of Pain and Emperor of all Maladies are two books I would really recommend.